Australian Chamber Choir | Buckingham Palace

November 4, 2023, Basilica of St Mary of the Angels, Geelong

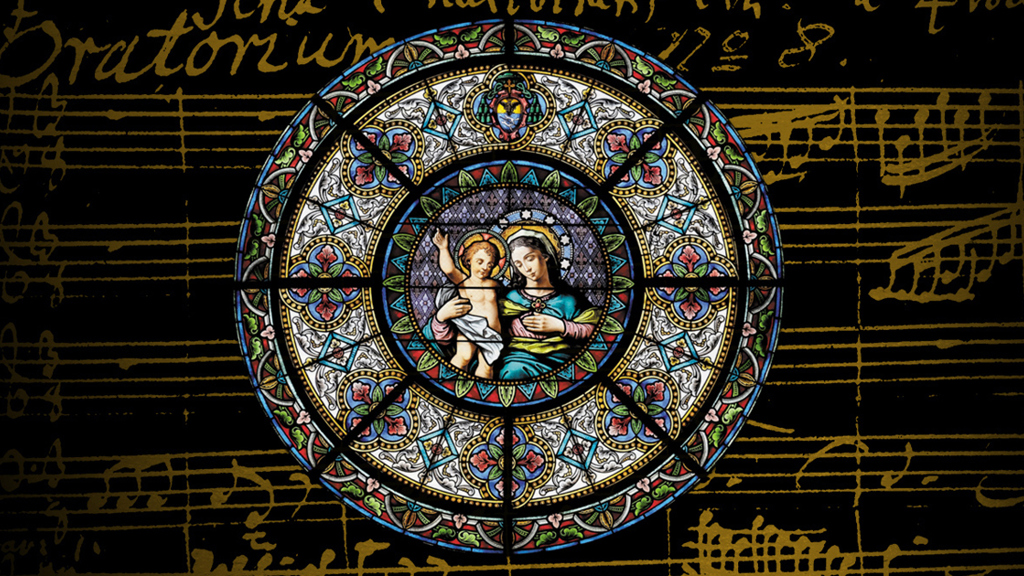

A coronation is a religious ceremony of the highest order, and, over several hundred years, the British monarchy have a storehouse of fine music from such royal occasions. Buckingham Palace (the title says it all) is the latest concert from the Australian Chamber Choir directed by Douglas Lawrence this time with Rhys Boak on organ and the David Farrands Brass Ensemble.

The Australian Chamber Choir, with the help of its Friends Program, make a point of traveling outside of Melbourne and touring the regions. This is admirable for many reasons, the least of which is giving me an excuse to get out of town for the day, have lunch with my mum and take in the concert with her friend and local music legend Maureen Zampatti at St Mary of the Angels, an impressive bluestone Basilica in Geelong.

The program was beautifully balanced between old and new royal music. Grouped into sections, the choir started a cappella with familiar works from the Renaissance and Baroque, including Rejoice in the Lord alway by John Redford, Purcell’s Thou knowest, Lord, the secrets of our hearts and Byrd’s Gloria from the Mass for Four Voices.

Douglas Lawrence showed his usual panache and a steady hand with the ensemble, effortlessly moving from one period to another. Hearing the beautifully balanced texture of the choir, I was reminded of how affirming it is to listen anew to works we know and love.

From the reign of Elizabeth II was John Tavener’s mysterious and medieval sounding Song for Athene (1993) and an equally serious setting of Psalm 42, Like as the hart (2022), by the Master of the King’s Music, Judith Weir. Both are works for funerals: the former for Princess Diana and the later for Elizabeth herself.

I particularly enjoyed the Song for Athene with its text based on Shakespeare by the Orthodox nun, Mother Thekla, a major spiritual influence on the composer. Sung over a drone the slow repetition of the Alleluia was reminiscent of Byzantine rites, minus the heady scent of incense. The works were well paired; although a little ironic, as the two royals were never close in real life according to the tabloids.

Ralph Vaughan Williams is well known by his own description as a “cheerful agnostic” even though he was dedicated to church music and a healthy relationship with the royalty of the day. O taste and see, is a setting of Psalm 43 composed for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953, with a fabulous opening solo, and the Sanctus from the Communion Service in G Minor (1920/21) which harks back to the Bryd heard earlier in the program.

Benjamin Britten didn’t appear to like to be bossed around by the British monarchy. Even though he was commissioned regularly, including the beautiful Jubilate Deo (1961) performed today, he knocked back multiple knighthoods and held out until he was offered life peerage. Perhaps he wanted to maintain his monogram on clothing, stationary and bookplates as the Baron Britten?

The Victorian and Georgian Eras encapsulated some of the finest sacred works from the English tradition, including Samuel Sebastian Wesley’s Thou wilt keep him in perfect peace and with its show stopping soprano solos, the Gloria (1937) by Charles Villiers Standford composed for the coronation of King George V.

For me, these works epitomise the soundtrack of royal fairytale, complete with organ and brass backing, both ancient instruments of power.

Having read up on the composer in the excellent program notes issued by the ACC’s Elizabeth Anderson, it was wonderful to hear the work We wait for Thy loving kindness, O God by the Melbourne-born organist and composer William McKie. Sir Mckie was born and raised in Collingwood and ended up directing music for both the royal wedding and coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. It felt like a teaser. I hope we hear more of McKie’s music by the ACC. A dedicated concert perhaps?

My soul, there is a country again by Charles Hubert Hastings Parry was sung at the funeral of Queen Elizabeth II and is a fitting song for our times. Parry is said to have been grieving several of his students who had been killed at war with his Songs of Farewell.

I was glad has been used at the coronation ceremonies since King Charles I in 1626. The Parry version builds on this tradition for the 1902 coronation of Edward VII. Although due to a timing malfunction (in the days well before the mobile phone or television) the anthem was over before the King had arrived and had to be repeated. I’m sure those attending didn’t mind.

Rhys Boak’s setting of The Old Hundredth could well become a royal inclusion, with its sweeping and surprising introduction and great modulations. Boak’s setting is majestic and harmonically interesting.

It is said that Ralph Vaughan Williams ‘outrageously’ persuaded Sir William McKie (from Melbourne, remember) to allow the congregation to join in the singing of the hymn at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. So I was so thrilled that for the encore, the ACC allowed us, the whole audience, to sing along to the new setting by Boak.

Singing along with Mum’s friend, Maureen, I could hear in the audience a fantastic tenor and contralto (surely trained musicians) in the row in front of us who appeared to sing along in parts. As Maureen said jokingly to the contralto we’ve all got a past, don’t we!

Not only was it a fine day for music, but for a little dining, sightseeing and talent spotting on and off the stage.

![user222 mrc mostlymozart [splendour of vienna] user222 mrc mostlymozart [splendour of vienna]](https://cdn-classikon.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/user222-mrc_mostlymozart_splendour_of_vienna.png)