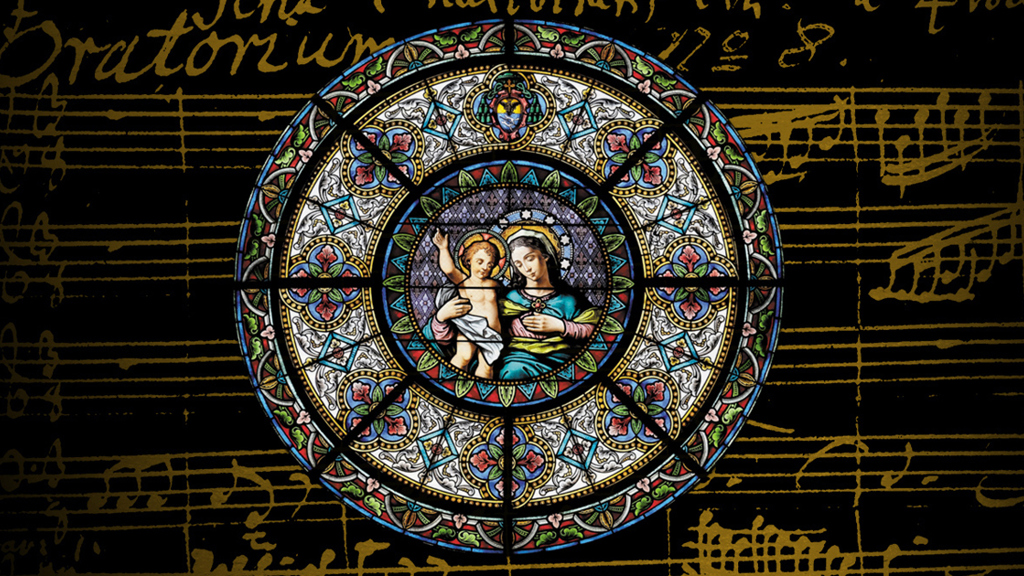

There can scarcely be a piece of music about which more has been written and postulated than Elgar’s Enigma Variations, which gave the title to Sunday afternoon’s concert by the Willoughby Symphony Orchestra.

Like so many famous works, it came about by serendipity as Elgar was experimenting on the piano when his wife arrived home and said how much she liked a particular theme. The composer then decided to write a set of variations on this theme; each one dedicated to and describing one of his friends. I doubt he dreamt of how popular the work would become.

Certainly, each section is superbly written and has a lingering quality which demands the listener’s attention. The ninth variation is entitled Nimrod, referring to the hunter of the bible; being dedicated to his best friend and publisher August Jaeger (German for “hunter”), it’s fitting that it is the most expansive and best known. Numerous detailed instructions are given to the orchestra and particularly the percussion. As the Orchestra’s conductor for the evening, Dr Nicholas Milton AM explained, the thirteenth variation is titled only by asterisks and probably refers to his first love. After much consideration, Elgar decided to use two coins on the sides of the drumsticks to recreate the sound of the engine of the steamer that carried his beloved away – originally these were half-crowns, but they’re a bit rare nowadays! It’s difficult to find a set of variations where each segment is so diverse yet so clearly related to the main theme.

Now to the enigma itself: Elgar hinted that there was a hidden tune hovering throughout the work and amused himself by not revealing it. He did deny a couple of attempts to solve the puzzle including one of Auld Lang Syne, but my favourite hidden reference is the suggestion of the theme of the Adagio movement from Beethoven’s Pathétique Sonata. Moreover, Jaeger had exhorted his friend to prevail over adversity as Beethoven had.

The work is immense in its complexity and freedom of expression – there is no hint of jingoism as shown in the encore, the well-known Pomp and Circumstance march – and it was handled superbly by the orchestra with a particular accolade to the percussion section which was kept busy throughout.

To start the evening, we were treated to Gershwin’s suite An American in Paris. If ever two composers were destined to meet, it was Ravel and Gershwin. They both thought very highly of each other’s work and together took a large part in the melding of jazz and classical music. The piece was written for a commission from the conductor, Walter Damrosch, who had actually asked for a full concerto as a sequel to Rhapsody in Blue. He was certainly not disappointed when Gershwin decided to write a piece combining jazz and classical idioms designed to portray the busy Parisian scene. Apart from a celeste and xylophone, there are taxi horns playing four different notes, while a saxophone emphasises the jazzy characteristics.

In the first part, there are references to music by Claude Debussy and a well-known Latin American dance theme. Although there are more introspective moments, the atmosphere is definitely zany. Reactionary critics at the time said that the music would not last and didn’t deserve to be in a concert next to Wagner and Beethoven. Well, as so often happens, they were proved to be quite wrong and, indeed the music featured in the eponymous 1951 film. Gershwin was later able to return the hospitality shown to him by organising Ravel’s successful tour of the USA. Amazingly, Ravel later in life never recovered from an accident with a Paris taxi!

Henri Tomasi was a twentieth century French conductor and composer and also in his early years made a living playing the piano with silent films, and in hotels and restaurants. His early compositions were religious in nature but the events of World War Two made him lose faith in God, and there followed a period of intense activity in which he wrote a saxophone concerto and also one for trumpet which he felt was a neglected instrument.

Rainer Saville is Australian born but is now based in Auckland as Principal trumpet with the Philharmonic Orchestra. He has also appeared as soloist in Europe, Asia and the USA. As well as having an interest in contemporary music, he also has studied and played Baroque and earlier works featuring natural trumpet.

The first movement of Tomasi’s Trumpet Concerto shows jazz influence and Rainer used two mutes of different timbre, often having to show dexterity in the interchanges. There is a very long cadenza in which the snare drum plays a part. The second, Nocturne, is more sedate with the soloist interweaving variations with the main theme. The Finale is boisterous and has runs reminiscent of hunting calls. Overall a very satisfying piece to listen to. We were then treated to a fascinating encore, a piece by Giacinto Scelsi which we were told represented the Muezzin calling people to prayer. Was this, I wonder, the first example of an Australian living in New Zealand playing an Italian piece calling Muslims to a minaret in Chatswood?

The playing of the soloist was faultless as indeed was that of the whole orchestra under its conductor with his unbridled enthusiasm, and what a varied and evocative programme we were treated to! A night to remember for all the right reasons.

Thoughts about:

![]()

![user222 mrc mostlymozart [splendour of vienna] user222 mrc mostlymozart [splendour of vienna]](https://cdn-classikon.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/user222-mrc_mostlymozart_splendour_of_vienna.png)