If there was a star-spangled concert in Sydney’s Early Music scene, this would be it. Madeleine Easton, Neal Peres da Costa, Mikaela Oberg, Alicia Crossley and Aaron Reichelt represented the best in their chosen instruments and they didn’t disappoint. What really struck me was how tightly the ensemble played – from the get-go to the last chord in the concert.

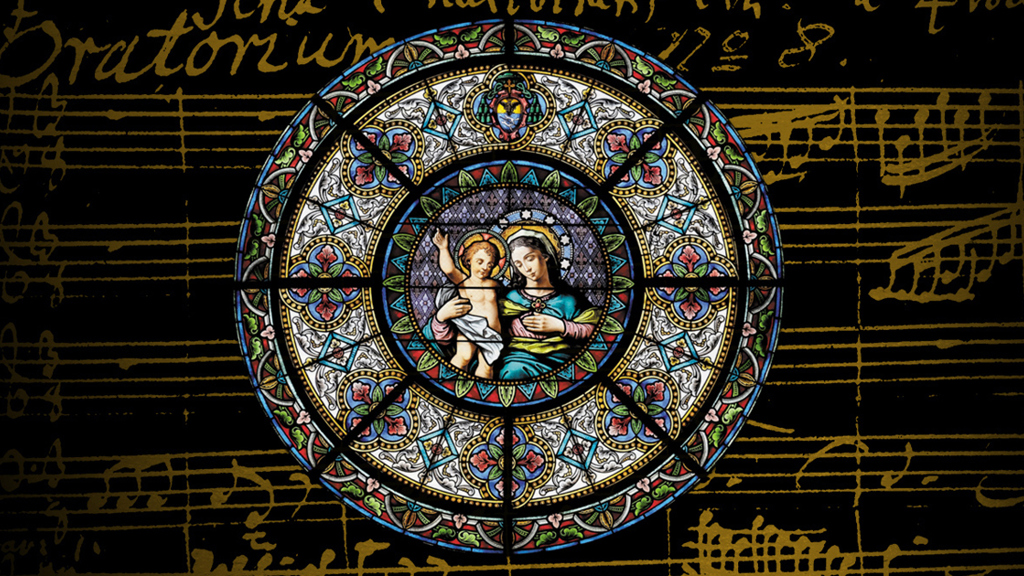

The programme of the concert was built on J.S. Bach’s Concertos, a musical form in which he excelled. With its strict formula of fast-slow-fast, there was a certain predictability to the music. The excitement lies in the curiosity as to what the composer will do with each instrument’s voice.

Aaron Reichelt was given the first spotlight as he showed his skills in Bach’s oboe d’amore concerto in A major BWV 1055. The instrument had a distinctive sound, mellower than the modern oboe one might hear in orchestral concerts. The pace of the first movement was quite fast, making it rather exciting. Reichelt steered the course with fast quaver notes, at times interspersed with legato passages, and didn’t shy away from Bach’s syncopation which he took with great precision. The slow second movement displayed the voice-like quality of the oboe d’amore which was deep, rather like a contralto. The players exuded tension in long, sweeping notes whilst Reichelt was the thread which held together the disparate lines of the other parts. When the fast tempo reset in the third movement, the audience felt the release of tension in the dance-like rhythm.

The short Sinfonia to BWV 182 “Himmelskönig, sei Wilkommen” was a dialogue consisting of recorders and violins. It was just a glimpse of what was to come in the Brandenburg Concerto. It was a foretaste of what was to come in the second half of the concert.

Bach’s E major violin concerto, BWV 1042 was one of the most recognisable pieces and a staple in the concerti repertoire. But the rest of the strings didn’t miss out from the spotlight. The effect was like a choir who at times let Madeline Easton, the soloist and leader of the ensemble, shine through. She didn’t really have a poignant role in the first movement, despite being the soloist, partly because the timbre of the violin blended too well, but mostly because of the writing. However, she made the most of her big cadenza. The second movement started with slow, solemn notes from the rest of the strings and continuo. She did have a more prominant role in this movement, by having the most lyrical passages as well as the one holding the tension. As in the fast pieces, the ensemble enjoyed the space and slowness of this movement and there was something lovely in the unhurried quality of its beginning and its end. The third movement was predictably livelier, and took the form of a song with clear delineation between soloist’s melody and ensemble interludes.

The instruments’ conversation was fully exposed in Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto no.4 in G, major. As a concerto, it was a unique piece in having more than one soloist. One could even argue that each line was a solo of its own. They brought Bach’s compositional genius to the fore in their intricate, unswerving lyricism. But if I had to give a vote, it would go to the second recorder player who played most of the counter melody in the second movement. In the third movement, they used the lively tempo, dexterity and trills to keep up the tension. As there was very little vibrato from the violins and recorders, the timbre was what cut through the busy texture.

Last to take the spotlight was Neal Peres da Costa, with the D minor Harpsichord concerto BWV 1052. He had been playing the accompaniment solidly in the concert, and it was interesting to hear the roles reversed. In this piece, the strings’ accompaniment was sparse, highlighting the dexterity and flourishes of the harpsichord. In the second movement, there were unison passages with the strings, making beautiful phrase arcs. Even in its own concerto, the harpsichord still accompanied itself. Finally there was a long passage during which the strings fell silent in the last movement. As I listened to Peres da Costa’s playing, I mused: harpsichord has a hard timbre to capture and to play. It’s also much more limited than a piano’s soundscape, so to make it sound beautiful and exciting is quite a feat. But the last note was Bach’s: he displayed his love for this keyboard instrument through the sheer length of this concerto.

Thoughts about:

![]()

Bach Akademie: Bach’s Concertos | Friday 4th October, 2019 | Paddington Uniting Church, Paddington

![]()

![user222 mrc mostlymozart [splendour of vienna] user222 mrc mostlymozart [splendour of vienna]](https://cdn-classikon.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/user222-mrc_mostlymozart_splendour_of_vienna.png)