When visiting art galleries across Europe one frequently comes across rooms full of commissioned military paintings: pompous men on horses or battle scenes on sea and land. While the painters may have significant technical skill, the subject matter often does not have any great emotional depth and so doesn’t really lend itself to great art. Usually, the ambulatory fast-forward button is pushed and one goes on to paintings where the artist has more control over the subject matter. It appears that there is an inherent dissonance between art and things military.

A chamber music program built upon “Emperors & Armies” did present me with some reservations. During the concert too, was some of the wildest weather the east coast has seen, where a tempestuous deluge broke the drought and, fortunately, put out the horrendous fires. Many of the potential audience however, did not brave the stormy weather and attendance was well down. Wild rain thundering on the roof did increase the warlike atmosphere of the program.

The fears of being musically assailed by guns, cannons and horses (think Tchaikovsky’s 1812, Holst’s Mars, Strauss’ Radetzky March) was ameliorated by the absence of any brass or percussion. After all, how much aural damage can a string quartet plus a flautist on period instruments do? Perhaps we were looking at a gentler monster…

The rather short opening piece, Boccherini’s Flute Quintet in D major, Op 19 No 6 “Las Parejas” is about a horse race rather than a battle, where the contestants are paired and have to hold hands for the duration. A strong unison opening in the first movement leads us to the introductory parade. With clever and well thought out articulation and tonal contrasts, the ensemble worked hard to give shape to a score which is often rather matter-of-fact. The actual race, the second movement Galope, is in 6/8 time with an emphasis on delicacy rather than thundering hoards. This piece is not among the compositional greats. There are some pretty quirky rhythms, and the composer does not really feature the flute; it just fills out the texture.

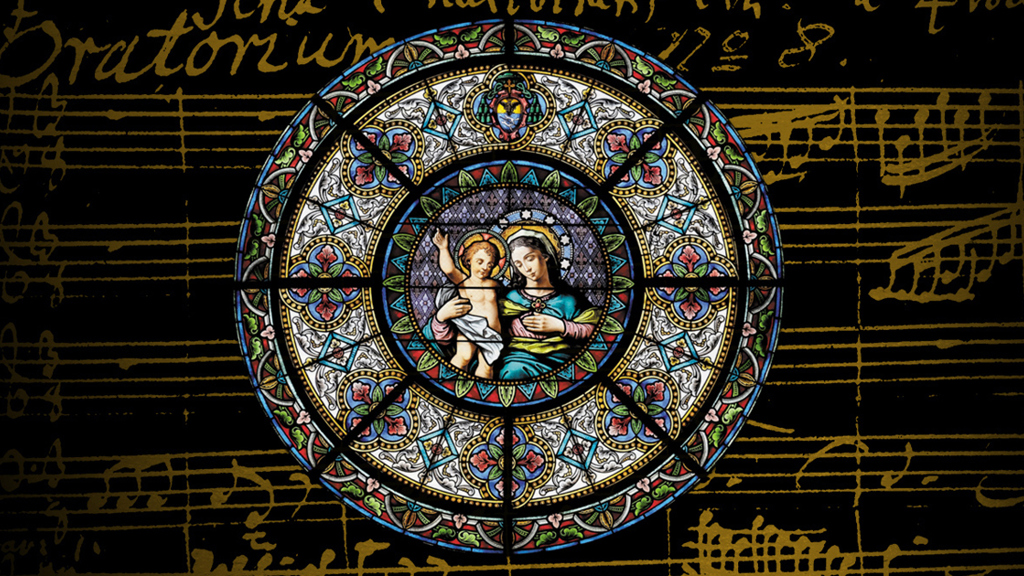

With Haydn’s Quartet No 62 in C Op 76, No 3, “The Emperor” we have a different kettle of fish altogether. This quartet is amongst the most famous of the genre, holding its place in popularity amongst Schubert’s “Trout” and Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet. What makes this work famous of course is Haydn’s use of his own composition of the Austrian national anthem as the basis for the second movement theme and variation form. The popularity of the quartet has probably made the Austrian anthem the most recognisable in the world.

The anthem and the quartet’s popularity notwithstanding; it is one of the masterworks of the repertoire. With both its popularity and quality comes a mountain of performance practice and the expectation that it must be performed a certain way. The AHE however, approached this work with an impressive freshness. They brought out things in the score that I had never noticed before. Their performance was rhythmically vibrant and joyful. Every opportunity was used to bring out contrast both at the phrasing and architectural levels. Individual voices were always clear but never at the expense of ensemble playing.

The Mozart String Quartet No 21 in D “First Prussian” was written for the Prussian king Frederich Wilhelm II, who was a gifted cellist. So cello solos are a feature of this work. Cellos are often an unassuming presence in a string quartet; less flamboyant than the violins, but secretly cellists know they are driving the bus. They are often the rhythmic anchor, and almost always the harmonic linchpin of the ensemble. They unobtrusively hold the whole thing together. One of the subtleties that I liked about Anton Baba’s cello playing was his use of purely tuned intervals, particularly descending fifths. These intervals are normally compressed (slightly out of tune) in equal temperament, but the beauty of fretless fingerboards, and without the likes of a piano present, is that when it counts, you can trot out a purely tuned interval, and Baba did this to great effect. The rest of the ensemble needs to adjust their tuning for this, but being the consummate musicians they are, they did this intuitively. Another tuning feature was the use of leading notes. These notes, which often lead to a new key by sharpening, can lend great harmonic pressure if they are slightly over-sharpened. Again, one cannot do this on a piano, but string players do this intuitively and it was used to great effect in Baba’s bass lines. Cellos rule!

The use of period instruments with their gut strings should be mentioned here too. They produce a much milder tone than the metal strings that became prevalent during the later 19th century. Also, the bows are held rather than gripped with the thumb, again bringing down the overall dynamic and brightness. That is not to say that the dynamic range is reduced; far from it, but it is altogether of a more gentle nature. Also, the players used vibrato sparingly. While vibrato certainly increases the intensity, it can also cover intonation problems which become more critical without vibrato, and early musicians must deal with this. Dissonances without vibrato do take on more bite however and the ensemble used such suspensions to great languid effect in this quartet.

Reduction scorings like those by Salomon of Haydn’s Symphony No 100 in G “The Military” were common practice in pre-musical recording days to make larger-scale music available within the home to amateur musicians. Often they were piano reductions, but here it is for flute quintet. The period flute, beautifully played by Melissa Farrow, is used to much better effect in this piece than in the Boccherini, in a sense carrying all the weight of the non-string sections of the orchestra within the single instrument. With this sort of military music, cheerful marching, minuets where one might image generals sipping wine while watching as the battle proceeds and the cutesy battle noises of the final movement. One cannot help but think that it is presenting a romanticised and sugar-coated version of war which makes the nobility feel good while doing nothing to represent the true horrors of war. Reduction or full symphony, this is no Mozart Dies Irae! Ignoring the moral and representational shortcomings, the ensemble did present a robust rendition in a purely musical sense.

I have already mentioned the cellist and flautist. Along with the leader Skye McIntosh and the ever-impressive Matthew Greco on violin and the sensitive viola of James Eccles (what an interesting-looking instrument!), this concert was a musically interesting and thought-provoking way to spend a stormy Sunday afternoon.

Thoughts about

![]()

Australian Haydn Ensemble: Emperors & Armies | Independent Theatre, North Sydney, 9 February 2020

![]()

![user222 mrc mostlymozart [splendour of vienna] user222 mrc mostlymozart [splendour of vienna]](https://cdn-classikon.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/user222-mrc_mostlymozart_splendour_of_vienna.png)