Australia Ensemble UNSW | Concert 1

22 March, 2025, John Clancy Auditorium, UNSW

PROGRAM

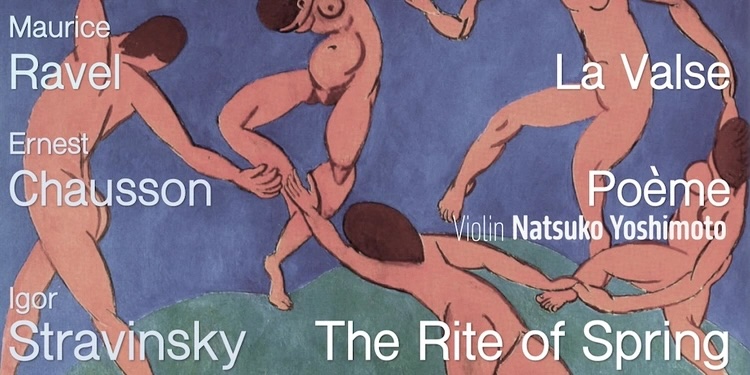

FAURÉ Piano Trio Op.120 in D minor

RAVEL Sonata for violin & cello

MESSIAEN Quartet for the End of Time

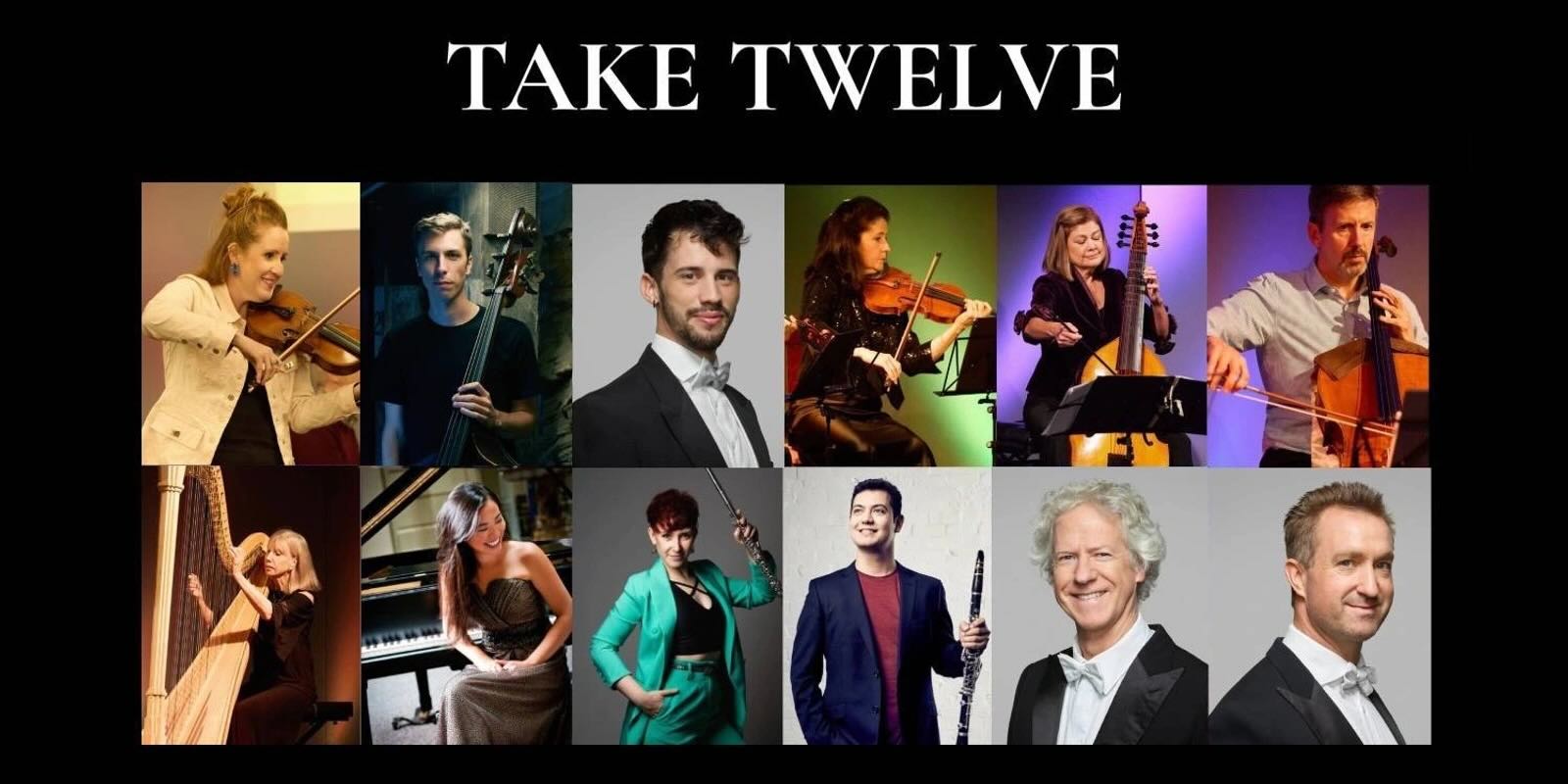

ARTISTS

David Griffiths, clarinet

Dimity Hall, violin

Julian Smiles, cello

Andrea Lam, piano

Three monumental works by French composers made for an expertly crafted program. The works by Fauré and Ravel were written in the aftermath of World War I and the Messiaen during World War II.

The Fauré Trio for clarinet, cello and piano was written when he was 78, about a year before his death. He was already not well and was not able to attend the first performance, but his fatigue does not show in this work. The strong unison opening and frenetic motion of the last movement certainly does not lack energy. The war had had a sobering effect though, and while the melodies in the first two movements are largely lyrical, there is none of the lushness of his Requiem or of Debussy’s harmonies to be found here.

The Ravel “Sonata” is in effect a duet for violin and cello, in this case for the husband and wife team of Hall and Smiles. Their performance was finely crafted and full of intensity.

Ravel saw this piece as a turning point in his music, leaning towards a pared back style where melody predominated over harmony. The formal structure of the movements is clear. The first movement is initially calm but, in contrast to the Fauré trio, its melodies are stark and sparse with harmonic twists within the phrases. The instruments interact melodically, often in the same treble range, rather than providing accompaniments for each other. The movement intensifies with increasing chromaticism and melodies with the same syncopated rhythms, but melodically wildly independent. Movement II is tumultuous with sudden outbursts and driving energy as is IV with Hungarian folk tunes in for good measure. The opening of movement III is like a two voice fugue, again in the upper ranges of the cello, but later deep and dark.

Olivier Messiaen famously wrote his monumental “Quartet for the End of Time” while imprisoned in the large camp at Görlitz in Eastern Germany. He wrote for the meagre resources that happenstance provided, other prisoners who had a violin, a cello and a clarinet. The Interlude, which became movement IV, was written for this combination of instruments. Then someone rustled up an old piano (with many sticking keys) which Messiaen used for most of the other movements, turning the work into a quartet. He was an organist, so he played the clunky piano himself for the first performance in the camp, in the bitter cold of the winter of 1941. They played for a large audience of both prisoners and guards.

The “End of Time” of the title refers to the apocalypse as portrayed in the Revelations of St John. Interestingly the Intermezzo is a pretty ordinary Scherzo, almost in the classical Viennese style; nothing apocalyptic about it. Perhaps he wrote this before deciding upon the overall concept of the work.

The abject misery of the war, the prisoners’ particular circumstances and the title of the work must certainly have been conflated with the end of the world. To this day, the work is usually seen in a similar light to other monumental works like Penderecki’s “Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima” and Britten’s “War Requiem”. Indeed there is strident chaos in movements II, VI and VII. But the work differs in one important way. While there is darkness, the work is at heart optimistic. Messiaen was a devout Catholic and saw the love of Christ as a constant, as portrayed by Smiles in the fifth movement with long sonorous phrases. The last judgment is seen as a prelude to the ultimate ascent into heaven. Hall played this last movement beautifully with the violin rising peacefully to the heights. Messiaen was also an ornithologist and birdsong, explicit in the treble instruments in first movement, but scattered throughout, holds an unfettered innocence and delight.

The whole performance was profound and utterly committed, but David Griffiths’ performance of the Clarinet solo (movement III) must be singled out. He ranged from depressive weary long phrases, through moving clarion calls to, again, irrepressible optimism in bird calls. Technically the most impressive thing I have ever heard on the clarinet was his crescendo from dead silence; it was impossible to tell when the silence ended and the note started. Awe inspiring.

The “Quartet” seems to have increasing relevance again today. Over population, global warming, water shortages, the hell being rained down on Gaza, Lebanon and Ukraine, and the Hitler-like intolerance emerging in the world’s largest superpower do not augur well for the future of humanity. And unfortunately even Messiaen’s religious optimism seems like a dream of the past.

But perhaps the birds will still be here after the coming apocalypse.