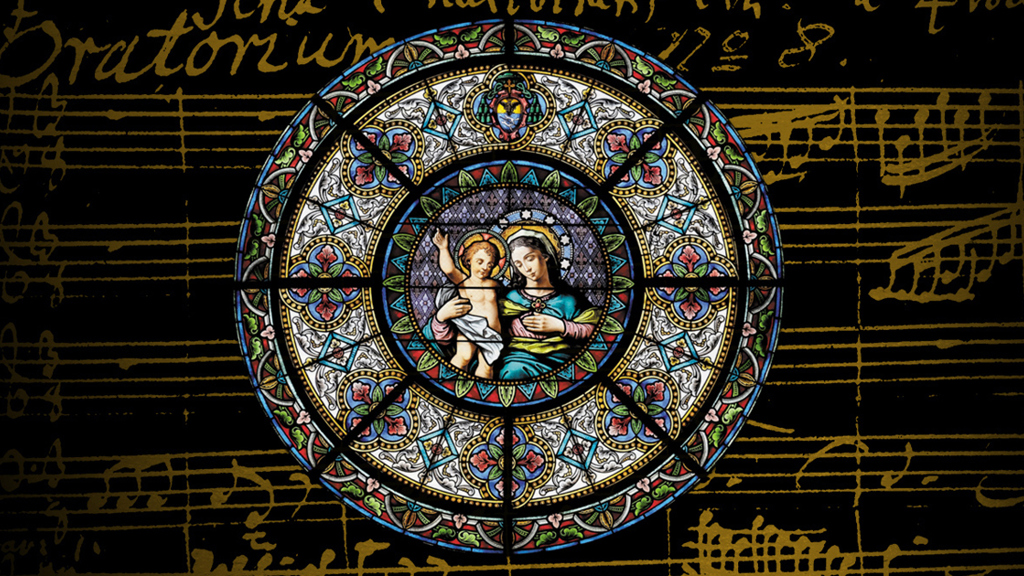

Thoroughbass presented once again a well thought through program of chamber music in their Bach in Three, which contrasted the work of the three biggest names in the Bach Family – Johann Sebastian (JS), Carl Philipp Emanuel (CPE) and Johann Christian (JC). The venue, Mosman Gallery, was perfect for such a performance – intimate and with a good acoustic, the former church with its stained-glass windows and high ceiling reminding us that JS Bach, father of the other two, viewed his composing as a life calling and spiritual ministry. He himself would have been very at home with his sonatas being played in this space. And like several in the audience, I had been wowed the night before in the Sydney Town Hall by the majestic and inspiring two-orchestra 250-voice performance of his St Matthew’s Passion. It was delightful to spend the following afternoon in an intimate setting listening to two of his sonatas.

Johann Sebastian Bach is recognised today as one of the greatest, if not the greatest, composer in the Western classical canon. It is difficult to believe now that he was not always regarded as the preeminent Bach composer – that accolade was accorded to CPE, a transitional figure between the Baroque and Classical periods, who wrote what was considered ‘progressive’ music – expressive, exhilarating, sometimes unpredictable – compared with the ‘old fashioned’ style of his father. Mozart is reputed to have said “Bach is the father and we are his children” referring not to JS as we would think, but to CPE. Both Haydn, ‘The Father of the Symphony’, and Beethoven acknowledged the influence of CPE’s compositions which they keenly collected. Thanks to Mendelssohn, JS Bach’s choral music began to re-emerge from the shadows in the 19th century and grew in popularity while CPE Bach faded from prominence and became the lesser-known composer. It is only in the last few decades that his work has been revived and featured in performances thus gaining the attention he rightly deserves, as the greatest composer of the Bach sons and a composer of great significance in the early Classical period.

CPE and JC were brothers, but there was an age difference between them of 20 years. After his father’s death, JC studied with CPE in Germany and through him was exposed to new musical thinking and secular cultural influences; he also spent time in Italy and then settled in England where he became known as ‘The London Bach”. These differing musical experiences influenced his development as one of the foremost composers in the elegant ‘galant’ style, popular across Europe post-JS Bach, and in turn influenced the concerto styles of Haydn and Mozart, who spent half a year with him as an 8-year-old studying composition.

I was very interested in this program by Thoroughbass because it provided an opportunity to observe something of the development of the sonata form from JS Bach through the progressive approach of CPE and finally to that of JC Bach. It was therefore unfortunate that the original order of the program was changed on the day with the insertion of JC’s work between those of JS and CPE. Nevertheless, the choice of pieces illustrated the development and it would be hard to imagine JS Bach writing a sonata in the style of CPE or JC.

The ensemble featured two violins (Stephen Freeman and Shaun Warden), viola da gamba (Shaun Ng) and harpsichord (Diana Weston). All are experienced musicians playing in the historically informed performance style. The program opened with two works by JS Bach. The first was his Trio Sonata for two violins and basso continuo BWV 1037. It should be noted that scholars now believe this sonata was written by JS’s pupil Goldberg, although clearly the master influenced the pupil. Typically, it has four movements, the melodic line shared by the violins, and the gamba and harpsichord providing the supportive line beneath. This was followed by his Sonata in B min for violin and harpsichord BWV 1014, which opened with beautifully played long slow drawn-out notes on the violin (Stephen Freeman), and featured a delightful interaction between the two instruments in the second movement. As Bach said of the trio sonata format, all parts “should work wondrously with each other”. The movements of the sonata alternated between slow and fast, and I loved the 4th movement (fast) with the harpsichord and violin playing off each other, reminding me of children chasing each other around a park.

The third item on the program was JC Bach’s Quartetto Op. 8 No. 4 from a set of six written for his good friend and gamba player Carl Abel, with whom JC founded the Bach-Abel concerts in 1765, soon the leading concert series in London. Here we can observe a very different approach to composition from JS, a mere 15 years after his death. There is far more expressiveness, more ‘conversation’ between instruments, and the harpsichord and gamba are viewed as instruments equal with the violins rather than primarily providing the supportive bass line. Although the Quartettos have only two movements, they are not ‘light and fluffy’ pieces, but very demanding to play in places. JC is less interested in polyphony, for which his father was renowned, and more interested in moving the emotions of the listener, as was CPE. But it’s an indication of how far JC Bach still has to go to get the recognition he deserves when one considers the first and only recording of his Quartettos was 2017!

The final section of the program was devoted to two works by CPE Bach. The first, which was the program highlight for me, was his Sonata in G min for viola da gamba and harpsichord H. 510. One does not have to be a gamba player to recognise how fiendishly difficult this sonata is. Shaun Ng gave a masterful performance of a work that exhibits the radical and progressive aspect of CPE’s composition for a specific instrument, perhaps written with a virtuosic gamba player in mind. We can also observe in this piece how CPE regards the two instruments as equals – this is not a sonata featuring gamba with obbligato harpsichord (as JS would have written it), but with both instruments interacting and taking the lead from each other. The harpsichord becomes two instruments, with wonderful melodic lines and runs for the right hand, leaving the left hand to provide the bass line.

The full ensemble regrouped for the final item – CPE’s Trio Sonata in E min for two violins and continuo H. 577. CPE was particularly fond of the trio sonata format, and the contrast with JS’s compositional style was again apparent in the way CPE uses the basso instruments not as supportive instruments but as full partners with their own rich melodic lines and harmonies. The second movement closes with a violin cadenza, and the third movement is typically CPE with its unexpected chord changes (perhaps to jolt any listeners nodding off in the drawing room after dinner?), rhythmic variations and dynamic shifts.

Bach in Three was a thoroughly enjoyable program which was enthusiastically received by the audience. There is the potential here, in my mind, for a slightly longer program but with an educational component added, outlining to the audience what to listen for as the program works through two pieces each from JS, CPE and JC Bach.

Thoughts about:

![]()

![user222 mrc mostlymozart [splendour of vienna] user222 mrc mostlymozart [splendour of vienna]](https://cdn-classikon.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/user222-mrc_mostlymozart_splendour_of_vienna.png)