Australian Haydn Ensemble – Mozart’s Prague

Saturday 18th December 2021

Sydney Recital Hall – Australian Digital Concert Hall

Skye McIntosh, Artistic Director and Concert-master of the Australian Haydn Ensemble compiled a ‘bold’ programme with Mozart’s Prague by virtue of the brilliant superiority, refined craftsmanship and exacting demands of the repertoire. The concert was streamed live from the City Recital Hall in Sydney by the Australian (formerly Melbourne) Digital Concert Hall, deservedly voted the People’s Choice in the 2021 Limelight Artist of the Year awards for their heroic support in preserving the livelihoods of musicians throughout the pandemic and maintaining connection with audiences around the world.

In his programme notes, Richard Bratby called Mozart’s Prague a story of two friends and three cities. The works by Haydn and Mozart stood out for exceptional quality, and the orchestra presented an unflaggingly stunning evening performance. The most outstanding aspect for me was the luxuriant sounds of the classical instruments and clarity of balance between wind, brass and strings.

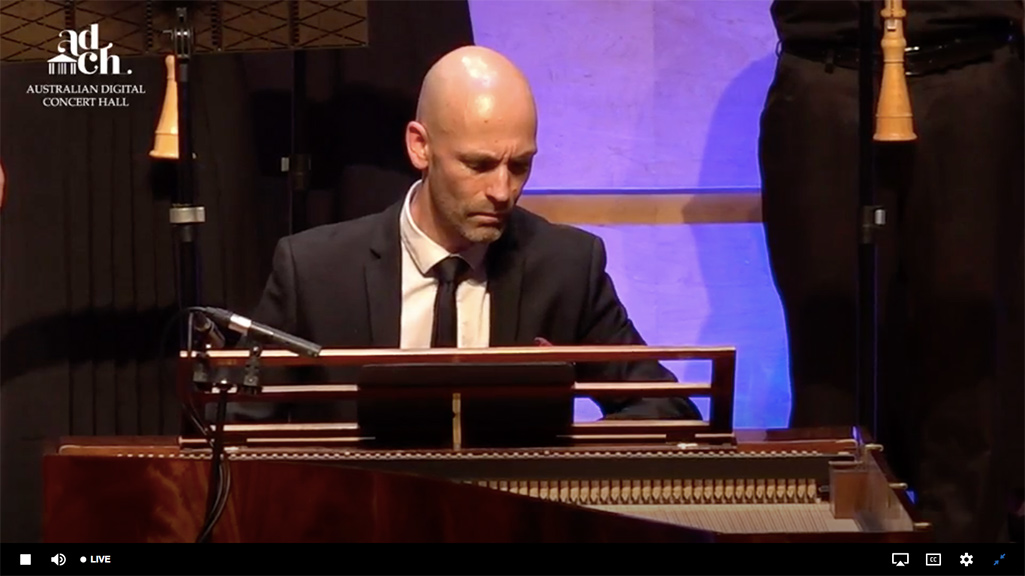

In 1790 Josef Haydn accepted an invitation to travel from his native Vienna to produce works for a concert series in London which culminated in twelve highly successful symphonies. The AHE performed his Symphony no. 95 under the direction of Erin Helyard, well-known Artistic Director and co-founder of Pinchgut Opera and the Orchestra of the Antipodes, and acclaimed as an inspiring conductor, virtuosic and expressive performer of the harpsichord and fortepiano, and as a lucid scholar who is passionate about promoting discourse between musicology and performance.

The opening arresting chords and pauses were loaded with dramatic verve, before the C minor tonality was immediately contrasted with endearing tunes in lyrical voice, displaying to good effect Haydn’s innovative designs of sensational extremes. Wind solos peppered the music, including wonderfully doleful tinges of Mikaela Oberg’s flute, sparkling oboe commentary (Emma Black and Adam Masters), appreciably discernible and euphonious bassoons (Simon Rickard and Brock Imison), delicate horns, and subdued trumpets and timpani. From the rich profusion of ideas, all instruments converged for a remarkably grand tutti ending in major key. A reflective Andante began with great gentleness in the strings, while solemn wind chords provided a subsidiary element to a dashing string variation, and added a sympathetic warming to the final pensive iteration. Another movement of ingenuity, the Menuetto comprised both a folky swing and air of disquiet. It was performed with excellent attention to its contrasting ideas and dynamics, with the Trio’s cello solo nicely phrased by Daniel Yeadon. The finale was a display of clever polyphony and received a performance full of bounce with yet more pleasantly prominent and exemplary playing from the bassoonists. Increased activity from woodwind, brass and timpani lent military force for a powerful and exhilarating finish. At moments, Helyard added to the orchestral colour with discreetly charming contributions on the fortepiano, unveiling a tantalising hint of the instrument’s sonority.

Thanks was expressed for the generous loan of the fortepiano (copy of an instrument by the celebrated Viennese maker Anton Walter) by friend and supporter of AHE, Ivan Foo. Mozart composed and gave the first performance in Vienna of his Keyboard Concerto no. 21 in 1785. Here, Helyard turned from conductor to soloist displaying to full effect the fortepiano’s incredibly rich and powerful lower register, vibrant high notes, and enthralling diversity of colour. He imparted a strong narrative with the fortepiano enjoying several passages on its own or with the barest accompaniment, in music infused with lyrical melodies and a wealth of virtuosic runs. The orchestra was a major participant in the spectacle, engaging conversationally with the awesomely beautiful themes, and adding march-like interpolations. An Andante of muted sighs and gentle throbs followed this abundance of energy, where lush tones continued to emanate from the strings, and wind phrasing was beautifully paired. The final movement imparted unbridled enthusiasm and radiant cascades of notes on the keyboard. Helyard’s cadenzas showed the fortepiano’s tonal range and sonority to advantage, the final one so harmonically audacious and as wittily ingenious as anything Mozart himself would have improvised.

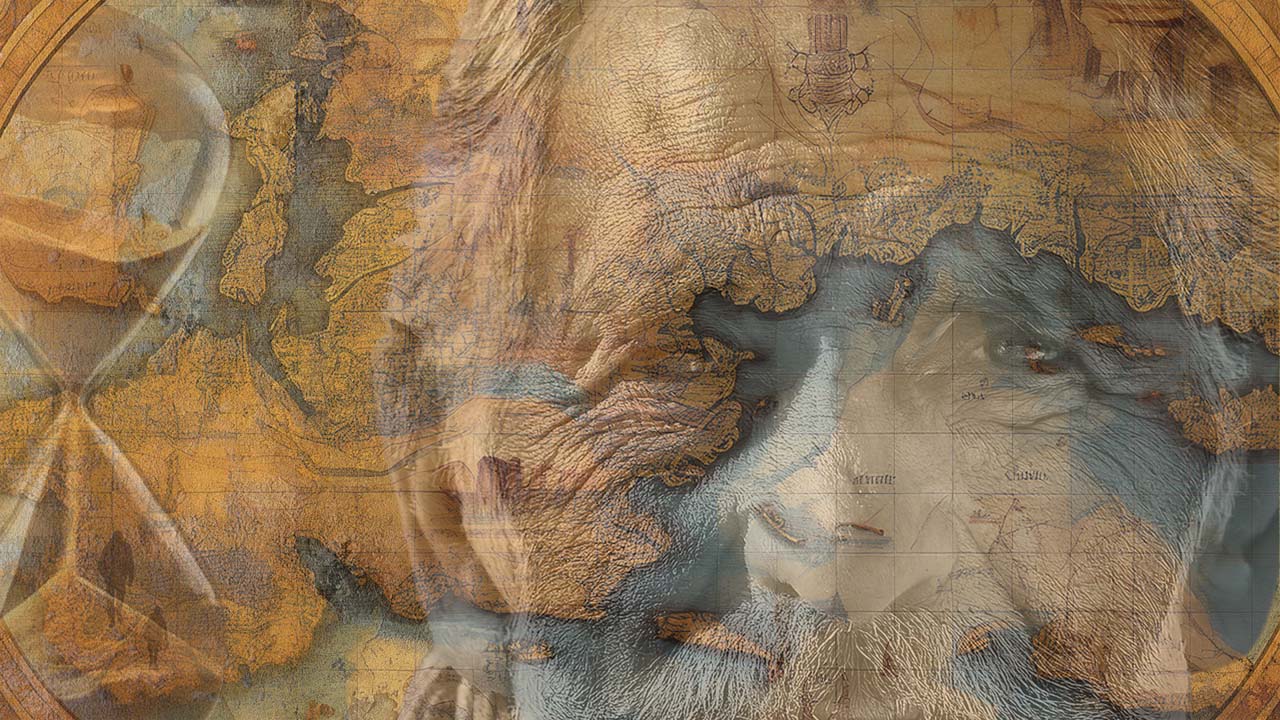

Mozart’s Symphony no. 38, another work of singularly dramatic proportions, took us to the city of Prague where it was premiered in 1787, a concert which elicited the approbation that “We did not, in fact, know what to admire most, whether the extraordinary compositions or [Mozart’s] extraordinary playing; together they made such an overwhelming impression on us that we felt we had been bewitched.” The first movement is one of ingenious complexity, bursting at the seams with a conglomeration of thematic layers, syncopated rhythm, rich harmonies and stimulating major-minor shifts of mood. These inventively combined elements along with Mozart’s generous and abundant use of the wind instruments and thrilling brass interjections painted a vivid scene. The AHE musicians paid due importance to the high sense of drama, giving an electrifying account of incredible clarity and coherence.

Helyard’s ad-libitum insertions on the fortepiano were judiciously apt in the tenderly flowing Andante, while the unwavering energy of the finale brought the concert to a triumphal conclusion. BRAVO! to the Australian Haydn Ensemble and Erin Heylyard for a formidably nuanced performance of convincing spirit and sophistication which the

music so rightly merits.