Queensland Symphony Orchestra & Circa | The Rite of Spring

21 February, 2025, QPAC, Brisbane, QLD

Performing The Rite of Spring as a collaborative venture with Circa was a smart move for the QSO. The promotion of this program has attracted considerable attention and there was a notable buzz of excitement as people claimed their seats. Prominent musicians were in the crowd including composer-conductor Richard Mills, acclaimed singer Katie Noonan and Brendan Joyce, artistic director and leader of Camerata – Queensland’s Chamber Orchestra. Significantly, there was also a bounty of noticeably younger ticket holders from mid-twenties to mid-thirties in tee shirts and jeans. Evidently, QSO’s management was confident the program could fill QPAC’s concert hall as it presented this event over three consecutive nights.

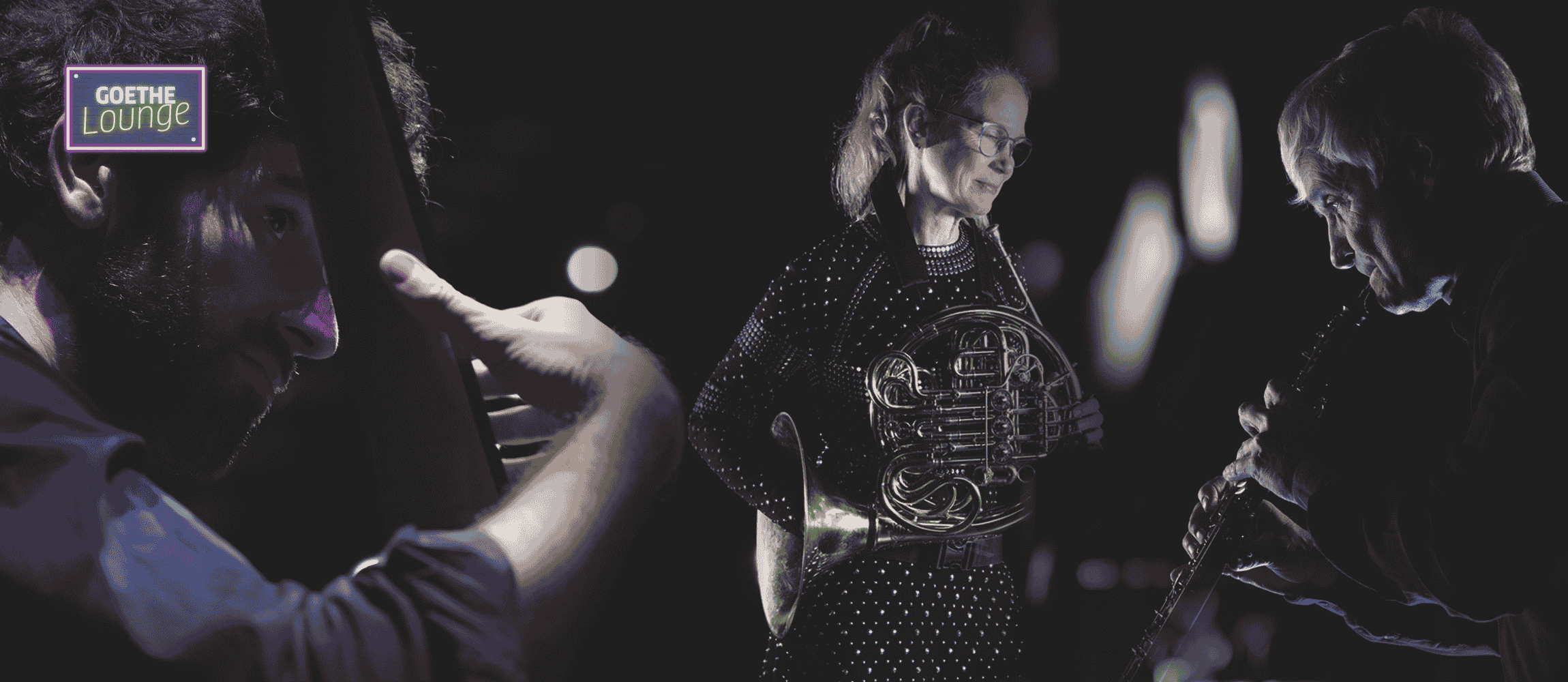

The program began with Debussy’s much-loved tone poem L’ Apres- Midi d’un Faun which he wrote in 1894. Alison Mitchell’s exquisitely languid, flute solo with which the work begins embraced the crowd. Inspired by Stephane Mallarme’s poem it represents a turning point in the history of Western art music in the same way the Rite of Spring sparked revolutionary new directions. Both works begin with a striking solo. In the Stravinsky, it’s a haunting melody which was beautifully realised by Nicole Tait.

Debussy’s subtle, evocative music with its whole tone scales and stretchy rhythm avoiding the tyranny of the barline, is in extreme contrast to Stravinsky’s rhythmically precise, spiky accentuation, harsh juxtapositions of multiple keys and lyricism paired with dissonance. While Stravinsky’s work was greeted by angry fists and boos in its premier, Debussy’s tone poem was rapturously received.

It was easy to see why Debussy and Stravinsky’s contrasting works had been programmed, especially as they had both been choreographed by Nijinsky as ballets. Less clear was the rationale for including Respighi’s rarely heard and arguably less inviting ‘Concerto Gregoriano’. Though perhaps it suggested itself by its celebration of unusual language in the form of Gregorian chant.

The Respighi work began in a similar meditative mood to the Debussy, with the QSO’s artist-in-residence and soloist Kristian Winther deeply engaged in channelling the music. Balances between the orchestra’s lighter and dense instrumental combinations were effectively brokered by Umberto Clerici who endearingly danced and swayed on the podium. The orchestra was alert and responsive to Winther and the conductor’s sincere championing of Respighi’s work. In the high speed third movement, Winther ‘shredded’ the violin with all the fervour of a brilliant guitarist in a rock group, and yet despite the skilled execution the audience’s reception seemed lacklustre.

Vibrant and on song in the concert’s first half after interval the orchestra burst into flames and flexed muscle, a primordial force screaming and pounding with razor sharp percussive swipes, spiky and bold and creating a maelstrom of bold colour in a dazzling account of Stravinsky’s polyrhythms and clashing tonality. Like a thrilling solo band it vividly narrated the plight of a young woman forced to dance herself to death in a brutal ritual sacrifice.

As a ballet The Rite of Spring has always been problematic for choreographers and dancers to stage successfully. Circa’s moves in the initial stages of Stravinsky’s work were suitably elegant but when the visceral pounding chords began the acrobats were static and awkwardly quivered and spasmed. But, as the brilliantly executed music journeyed on, superbly captained by Clerici, the dual force of musicians and athletes became closely meshed with some daring athletic moves, women hurled in the air, bodies tangled and writhing on the floor. And, as the young woman dances her self into sacrificial oblivion there were astonishing sequences in which she flipped over backwards and forward multiple times and perfectly in sync with the brawling music. A well-deserved standing ovation greeted this exciting, daring, unusual and highly polished performance.

Photo credit: Sam Muller